Translating a Just Transition Into Contractual Relationships: Contractual Solidarity as a Pathway to Sustainable Contract Law?

The climate and environmental crisis affects people unevenly across the globe. A just green transition must therefore ensure that no one is left behind. In this guest blog post, Jie Ouyang (RUG) explores how the idea of solidarity can inform our understanding of a sustainable contract law.

Introduction

This blog post examines the role of contractual solidarity in promoting just and sustainable consumption, particularly its potential and limitations in distributing the costs of the green transition. I will follow a pragmatic definition of solidarity: ‘Social solidarity envisages the inherently uncommercial act of involuntary subsidisation of one social group by another’ (AG Fennelly to Case C-70/95). Two core characteristics can be observed in this definition. First, solidarity entails an involuntary duty inherent in interdependent relations. Namely, to prevent such relationships from collapsing from within, actors involved must display a degree of solidarity towards each other, irrespective of (individual) consent or choice. Second, social solidarity centres on the cross-subsidisation amongst different social actors or groups, usually based on their relative capacity to contribute. It is therefore often associated with social policies that feature resource pooling and risk sharing, such as healthcare or unemployment benefits.

This definition explains why solidarity is not a frequented concept for private lawyers, especially for contract lawyers (though see Veitch and Leone; French jurists also seem to be more comfortable with this language). Contracts are traditionally understood as consensual and reciprocal exchanges – an understanding that appears fundamentally at odds with involuntary subsidisation. Yet solidarity is a core constitutional value in the EU legal order (see Art. 2 TEU). Notably, the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights contains a dedicated chapter on solidarity rights, including inter alia environmental (Art. 37) and consumer protection (Art. 38). Against this backdrop, it seems relevant to explore whether or not solidarity has – or should have – a role to play in (European) private law, especially when it comes to sustainable consumption.

From contractual embeddedness to contractual solidarity

So should we consider solidarity in contractual relationships? Since solidarity arises from interdependence, any discussion of contractual solidarity should be preceded by an enquiry into contractual dependence. I argue that this dependence is best understood as the double embeddedness of contracts: their internal, relational embeddedness and their external, material embeddedness. On the one hand, contracts are embedded in the interpersonal dynamics between the parties: Are the parties equal in bargaining power? Are their interests aligned or adversarial? How long does the relationship last, and what purposes drive the contractual venture? On the other hand, contracts are externally embedded in the broader socio-ecological systems in which they operate and to which they feed back. As Durkheim famously puts it, ‘Tout n’est pas contractuel dans le contrat’ (not everything is contractual in a contract). The realisation of contracts relies on collective systems of cultural meanings, social cooperation, institutional enforcement and natural provision, while external factors – from strikes to shifting social norms to extreme weather events – may directly frustrate the basis of contractual arrangements. Meanwhile, contractual performance often produces significant negative externalities for third parties and the environment.

Importantly, these internal and external dimensions are not merely parallel but mutually constitutive. How the parties internally arrange their terms shapes the fate of contractual externalities. Conscious contract design and drafting thus have great potential in producing responsible contractual practices, while harsh contract terms (e.g. low prices, high order volumes, short delivery times) can exacerbate risks of forced labour, human trafficking and environmental non-compliance. Conversely, external conditions shape how parties experience contracts internally. We are all consumers, employers and tenants – but women consumers pay a ‘pink tax’, religious employees may be forced to refrain from certain practices in deference to workplace neutrality, and foreign tenants face higher risks of eviction. Putting in doctrinal language, appeals to the principle of formal equality may abstract parties from the material realities that shape their contractual experience. Similarly, a rigid reading of contractual privity and a static application of pacta sunt servanda also serve to obfuscate both the material reliance and the material impact of contracts on society and nature. Hence, when contract law institutionalises the abstraction of contractual relationality from contractual materiality, the freedom of contract enables contractual extraction.

It is against this background that contractual solidarity becomes normatively salient. From relational embeddedness emerges an obligation of internal solidarity – an obligation to take the other party’s interests into account and sometimes even to act altruistically. Doctrines like good faith, the duty of cooperation and the prohibition of abuse of rights capture this idea. The materialisation and constitutionalisation of private law increasingly help portray private law persons as socially and constitutionally embedded selves, though structural and systemic inequalities remain insufficiently visible in private law. At the same time, contract law is not entirely insensitive to the material reality and the external solidarity it imposes: rules on change of circumstances enable post-contractual redistribution of contractual risks; the third-party beneficiary doctrine allows affected third parties to hold contractual parties liable; and public order invalidates the most socially and environmentally detrimental contracts. However, while these doctrines can, in limited cases, serve to internalise contractual externalities, it is often unclear how the internalised costs should be fairly distributed. This tension surfaced, for example, in debates during the pandemic over whether passengers should accept vouchers rather than compensation as an expression of solidarity.

Sustainability as contractual solidarity? The case of the value chains of fast fashion

With this framework in mind, I now move on to discuss whether sustainability can be viewed as a form of contractual solidarity. Recall that solidarity involves involuntary duties and capacity-based cross-subsidisation. Two questions then follow: First, is it possible to impose a duty of sustainability on contractual parties, irrespective of their contractual incorporation or explicit consent? Second, to what extent can contracts contribute to a fair distribution of the costs of sustainability?

On the first question, a universal duty of sustainability becomes less controversial in jurisdictions with an explicit ‘green principle’, as in China, or with a codified notion of ‘environmental public order’, such as Belgium. However, the greening of private law does not always require a revision of the civil code. For example, the French Supreme Court has recognised a private obligation of vigilance with regard to ‘any damage to the environment that may result from their activity’ based on the country’s Environmental Charter. As more legal systems constitutionalise environmental rights or even climate obligations (as endorsed by the ECtHR and the ICJ), similar horizontal reasoning can arguably become more widespread. Even without directly revoking constitutional norms, judicial discretion in interpreting and supplementing contract terms can also serve as a gateway for sustainability duties. The District Court of Amsterdam, for instance, inferred a buyer’s obligation to place orders – despite the absence of an explicit clause – based on the buyer’s CSR commitments to labour protection and the seller’s economic dependence on those orders to avoid dismissing workers (as the seller receives orders almost exclusively from the buyer). In other contexts, public law standards can inform a more normative and objective assessment of private law norms – think of the interaction between ecodesign requirements and contractual non-conformity.

The second question will be illustrated through fast fashion. Global fast fashion value chains are notorious for price squeezing and unequal value distribution, with factory workers – especially in the Global South – bearing the brunt. For example, research shows that, for a T-shirt of 29 euros, only a staggering 18 cents are paid to workers, while it only takes less than 1% of the retail price to pay factory workers a living wage. The question is: who should pay this 1%?

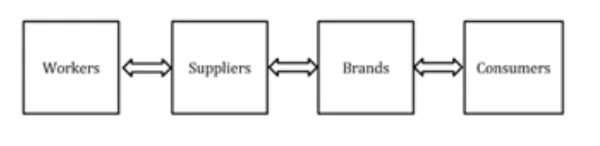

Consider a simplified contractual chain. In principle, suppliers, as direct employees, should meet their legal and contractual obligations towards workers to pay an adequate wage. In practice, however, they often lack the real capacity to do so because of the harsh conditions imposed by lead firms. For suppliers and workers alike, it is often a choice between low prices and no contracts at all. However, if workers bring direct claims against global brands as third-party beneficiaries, they will unlikely succeed, as exemplified in the Walmart case. These realities then shift attention to lead firms to behave better, and one way to do so is through the incorporation of responsible contract terms: for example, the Model Contract Clauses (MCCs) 2.0 require pricing terms to accommodate costs of responsible business conduct, like living wages and environmental compliance. Yet their uptake remains voluntary, and enforceability uncertain. While emerging mandatory due diligence regimes will likely implicate contractual practices, little has been said about the most harmful pricing practices. Then consumers come into the picture: responsible production usually leads to higher prices for consumer products. While it is justified to limit consumer access to ultra-cheap fast fashion – cheap only because of the massive externalised labour and environmental costs – how do we make sure that the higher price tag actually contributes to fair and sustainable conduct, instead of simply preserving corporate profit margins? Asking individuals to pay more while big corporations maintain the same level of profits hardly reflects a fair distribution of solidarity burdens.

While I use the example of fast fashion, the same logic applies to other cheap products – think of budget airlines, plastics or meat. This analysis highlights both the potential and the limits of contractual solidarity in distributing the costs of sustainable consumption. How to meaningfully integrate principles such as common but differentiated responsibility into private law remains an open challenge. Contracts matter – they function to structure solidarities in our world of contracts – but contractual solidarity must ultimately be embedded in broader regulatory frameworks, distributive safeguards and social movements if it is to support a genuinely just transition.

0 Comments